a lost study of soviet subway construction

As someone who grew up in a city of Soviet-era subways, I have a nostalgia for the engineering innovations that shaped its unique infrastructure.

The 1917 Revolution and the following Civil War substantially deteriorated the manufacturing and transportation industries with a sharp outflow of the urban population to the countryside. In Moscow alone, from 1915 to 1920 the population decreased from 2 to 1.1 million people with the average annual number of trips by public transportation of about 21 compared to 197 before the wars. (MPI) As enterprises gradually resumed operations, people began flowing back to the cities from the countryside. But Moscow soon faced a major transportation crisis, unable to meet the needs of its growing population.

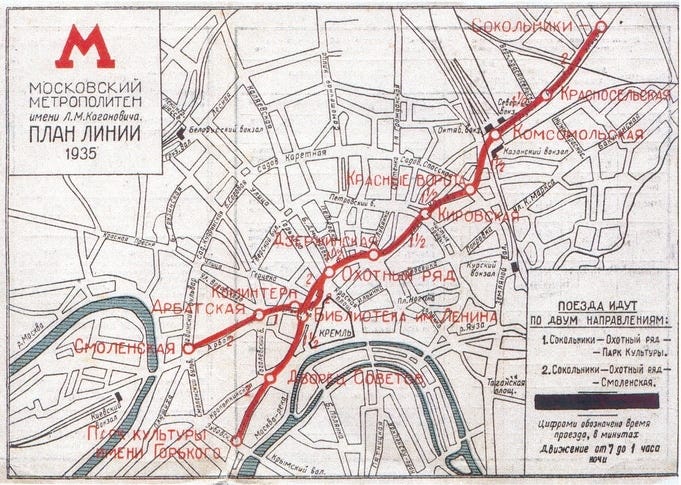

In response, Moscow's City Council formed a small subdivision to design a metro system for the city. On Christmas Eve 1931, a transport collapse occurred, forcing Stalin himself to address Moscow's transportation woes. He instructed officials to develop plans for a subway system. The following August, Metrostroy was established to oversee the project, headed by chief engineer Pavel Rotert. Rotert negotiated the release of imprisoned Moscow railway engineers to work on the new metro system. With this influx of talent, Metrostroy set out to build Moscow's first subway. (O'Mahony)

How to Build?

Initially, it was essential to decide how to build the subway. By the 1930s there were three main schools of metro construction: London, Paris, and Berlin. These did not interact due to different soil conditions in the three capitals, as well as differing national construction traditions:

The London method was considered the most advanced, involving shield tunneling machines suitable for the favorable mining and geological conditions there - dense clay at a depth of 20-30 meters.

The Parisian version involved shallower tunnel construction, known for a long time, using laborious and dangerous manual mining methods with temporary wooden supports. The tunnels and stations were then lined with stone and cement.

In Berlin, the wide, straight streets and geological conditions (flooded coarse sands) enabled the simplest and cheapest open trench method, with artificial groundwater lowering. (Federal Transit Information)

A debate arose within Metrostroy about the best approach. The London method was immediately discounted since the USSR lacked the necessary shield machines and could not build its own or establish mass production of cast iron tubing. The technical department had to choose between the remaining methods, weighing many factors:

narrow, crooked streets in the city center;

the lack of a general plan, work on which was just being carried out;

extremely complex Moscow geology with quicksand soils, absolutely different from the geology of Paris and Berlin;

almost complete absence of a production base for construction;

total shortage of materials;

lack of qualified personnel;

lack of housing for hired workers in overpopulated Moscow

soon the most important factor: not a single decision could be made without

agreement with the "masters" of Moscow - Kaganovich and Khrushchev, the main associates of Stalin

Realizing all this, Rotert decided to start small. He inclined towards the Berlin open trench method, knowing it was unlikely feasible downtown. Instead he decided to build an experimental shallow, single-vault tunnel for two metro tracks, using the mining method per the Moscow City Railways proposal - even before the whole project was designed. (Moscow City) Arguably, innovative and creative thinking emerged despite the government constraints and resource shortages.

Construction Challenges.

Construction proved difficult and soon halted after an accident involving ground subsidence and a burst water pipe. In March 1932, a young engineer Veniamin Makovsky, who favored deep shield tunneling, appealed directly to the Moscow Party citing frustration with Metrostroy leadership. His proposal was approved by Khrushchev, Kaganovich, and Stalin. Rotert failed to convince Stalin that shield tunneling was impossible to implement quickly, and had to redesign the whole line as a deep tunnel (requiring extensive further geological surveying). Construction of deep access shafts began along the route. However, it proved impossible to simply transfer deep mining methods to the city. The resulting subsidence was untenable. (Moscow City)

All the shafts fell hopelessly behind schedule, with some stopping entirely. It became clear this method would not work either. To find a solution, three foreign expert commissions and a domestic one chaired by geologist Ivan Gubkin were convened. The foreign groups unsurprisingly advocated their own methods. Only Gubkin's commission was flexible, recommending deep tunnels downtown but variable methods elsewhere based on conditions. This led to completely revising the designs again, with full-scale work only resuming in summer 1933. The initial lack of communication between government and technical leadership caused unnecessary redesign costs and delays. Moreover, many issues arose from the failed policy of resource allocation and workforce planning: (O'Mahony)

Rolled steel shortages forced the use of log supports in pits, suspending exposed pipes and cables from them. This precluded excavator use, requiring manual or primitive winch digging.

There was a catastrophic lack of tools to remove the excavated soil, which accumulated dangerously at pit edges. Later, all freight transport in Moscow was obliged to help remove soil, with trams also used at night. Providing more funding and transport infrastructure, collaborating with foreign partners, or extending the schedule could have addressed this.

Additional construction methods like blasting and chemical soil solidification were dangerously employed. Continuous pumping from wells inside or around pits was required for drainage. Better technical consultation and planning for worker safety could have mitigated these risks.

Despite the challenges, constructing the Moscow Metro's first stage gave powerful momentum to developing various industries:

In a very short time, Soviet enterprises developed new rolling stock, automation systems, and escalators for the lines.

The metro required huge amounts of construction and finishing materials, spurring production.

The metallurgy industry increased production of steel profiles and mastered cast iron tubing, used extensively in the second stage.

A new architectural direction emerged, as the stations were built as 'underground palaces for the people', with highly ornate designs. Many prominent architects participated, blending Baroque and neoclassical influence with Socialist themes. Decorative elements in the stations included chandeliers, mosaics, marble walls, ceiling frescoes, and ornate cast bronze latticework. This 'Stalinist Empire style' set a model for future Soviet monumental architecture.

Enduring Influence.

The Moscow Metro's construction was an enormous undertaking that revealed both the possibilities and pitfalls of large-scale centralized planning. Despite numerous setbacks and policy missteps, perseverance and creative problem-solving by engineers, architects and workers on the ground ultimately achieved success. Mass mobilization of resources showcased Soviet might, but breakthroughs often came from individuals.

The Metro stood as a symbol of modernization and efficiency, improving urban life for citizens. However, the lavish architectural designs aimed primarily to showcase state power rather than uplift workers. The human toll of the project was also immense. Still, constructing this complex rapid transit system under severe constraints demonstrated that shared purpose and determination can accomplish extraordinary things. The Moscow Metro would emerge as a point of pride, its palatial stations proclaiming the Union's engineering prowess and grand ambitions.

Sources:

O'Mahony, Mike. “Archaeological Fantasies: Constructing History on the Moscow Metro.” The Modern Language Review, vol. 98, no. 1, 2003, pp. 138–150. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3738180.

Moscow City, “Building the Moscow Metro, or the Brief History of the Underground City / News / Moscow City Web Site.” Moscow City Web Site, Mos.ru, 13 Sept. 2017, www.mos.ru/en/news/item/28604073/.

Wikipedia, “Moscow Metro.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moscow_Metro.

MPI, “A Migration System with Soviet Roots.” Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/russia-migration-system-soviet-roots